This is, of course, an unfair fight.

The British Museum has long brought a knife to a gun fight. A tradition in history, documenting, archiving, and an obvious affinity for achaeology must have served them well from the 1800s… But when it comes to designing exhibits, in 2014, I think they could use some help.

The Royal Academy, however, put on a fairly amazing show, and that is what I will be comparing (sort of comparing, it’s apples and oranges really) the BM Viking exhibit to.

Here are some things they could have done much better, to ensure visitors left uplifted, having learnt something, felt something, instead of being exhausted.

The single biggest flaw of the British Museum exhibits is this: Imagine a large room, a glass box, a small card with a description, a queue of people waiting to read the card, see the item, and exclaim “oh my!”, before they repeat the process another hundred times, in sequence.

Back when they’d found Tutenkhamun’s tomb, that may have worked wonderfully. Museums were for those with time for leisure, and the special exhibits, one can only assume, were as extortionately priced as today, limiting the crowds further. In those days “crowd” was a few hundred people. Not a few hundred people every 30min.

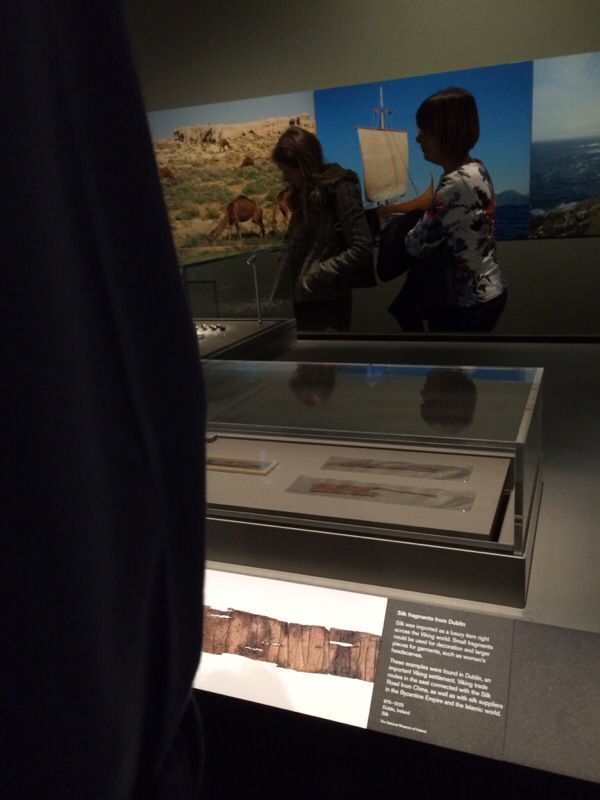

People crowding around the first piece displayed in the Viking exhibit at the British Museum.

This weekend, I went to two exhibits. On Saturday, 8 of us went to the Viking exhibit at the British Museum. We were all forced to buy the audio gude (a bonus £4.50 on top of the £17 we had already paid) so that we could maybe understand some of the things we were about to see.

8 people. £21.50 each. That’s a magical £172 for the museum, right there!

poor labelling made everyone tired

Every single one of us found the little signs were:

– constantly blocked by people’s hands, hips, coats, shadows, etc…

– too small to read comfortably (I kneeled at one point. And a doyenne had a hard time bending over, despite her petite frame, to read those minuscule panels. I felt bad for her.)

– on one occasion, conflicting with what the audio guide was saying (a hog stone is shaped like a boar according to one, like a house according to the other. I would imagine both are valid)

– making us sad (constantly looking in the direction of the floor makes one sad. Try looking up, count to 10, look back at your screen, and tell me if you feel at all uplifted. Try it next time you’re walking down the street feeling miserable.)

– to a small extent confusing, because there were no numbers linked from the signs to the items in the display cases, despite some cases having numerous signs, or numerous items. Are the librarians losing their touch?

I did notice the signs being used pleasantly and very well by a small subset of the museum’s visitors. Everyone between the ages of 6 and 11 was enormously pleased with the size and position of those labels. I only wish there had been a disclaimer at the entrance: “designed for kids”.

Or perhaps a better way to visit would be on a little train that moves everyone along at the right height, eye level with the cards. Or should it be eye level with the exhibits? And that’s my point, right there! Why isn’t everything on the same level?

keep labels on same level as exhibits

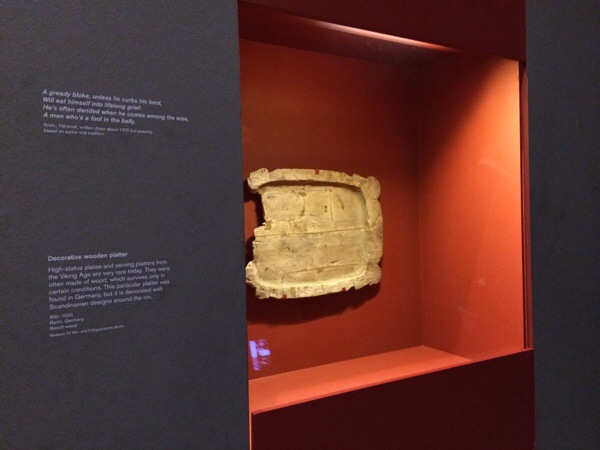

Between the first and second half of the exhibit, there was a little corridor. There, the glass cases had the descriptive text printed alongside them, on the wall, at the same level. That worked wonderfully well, as you could read, move over, see the object, and move over to the next one. The sequence of read-look-next moved you along the corridor.

memorable quotes became features on the walls

So as not to complely diss the British Museum (despite this being my second experience of a very poorly thought-out and labelled exhibit – if you saw the book of the dead, you might remember a similar labelling issue), there were a few things that were very well done.

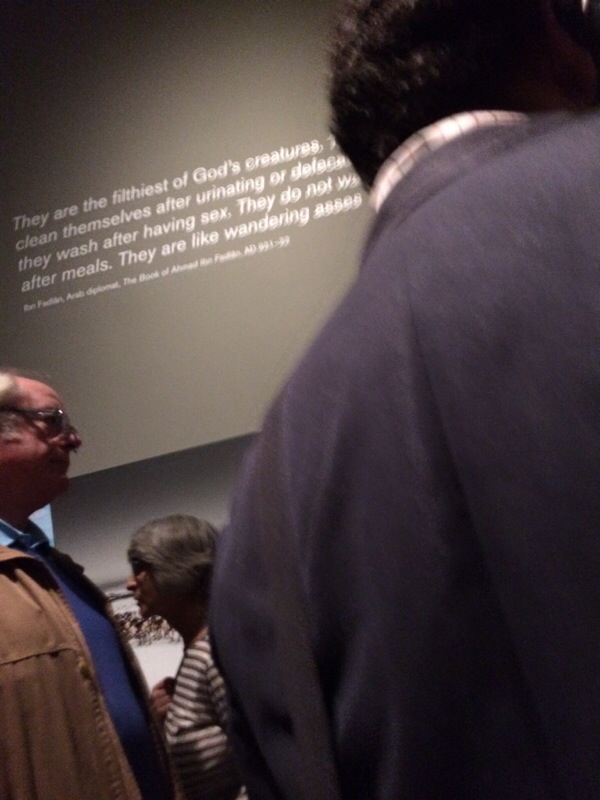

Across the exhibit, beautfully-lit quotes were printed high up on the walls. I expect many people saw those. Between the boredom of waiting to read the next little card and the attractive lighting, they caught your eye.

My favourite read: “They are the filthiest of God’s creatures. They do not clean themselves after urinating or defecating, nor do they wash after having sex. They do not wash their hands after meals. They are like wandering asses” Ibn Fadlan, Arab diplomat, The Book of Ahmad Ibn Fadlan, AD 991-99.

It is my favourite because it reminds me of something my dad used to joke about sometimes “when we were building the Parthenon and using plumbing, you were wiping your arses with leaves”. This can be applied to nearly every population north of the Balkans in Europe. Yes Greeks are, on occasion, a little bit smug.

Further into the exhibit, some video displays and sketches illustrated several processes and pieces of trivia (such as where starboard comes from: the side the steering oar was on a Viking ship, in the back, to the right) really well. It wasn’t all terrible! Just part of it.

make the most of what you already have

Two women, meanwhile, had a brilliant idea. They spotted the “large font books” or whatever they are called, and were walking around the exhibit reading those and looking at the items from a slightly safer distance. They could read the description in their own time and space, step in for a few seconds to look at the item, and step away again. It diluted congestion. I was grateful to them for the reprieve and jealous of their method.

Meanwhile, I had the useless audio guide hanging around my neck. In the first half of the exhibit we might have used it 6 of the listed 18 times? And the first half of the exhibit was the badly labelled one.

I wished then, that the museum had made use of its meticulous labelling of every single display case, and of my smartphone-based guide, to give me an electronic index, perhaps even with images, of the items in the exhibit. The same text they have on the labels, but electronically, in my hand, on demand. Much like the ladies’ massive book, but small. That was a missed opportunity.

Another missed opportunity is the amount of space wasted on each of the “bars” under each case. The text could have been much larger, no?

help people learn

This is an obvious one, and odd that it wasn’t done in this instance when it was done a few other times. This piece of bark has a runic inscription on it. They showed the piece of bark. They also showed a photograph of it on the child-level (sounds better than crotch, doesn’t it?) labels. What they forgot though is to add an illustration that shows what is written on it in a simplified way, so we could learn to map the futhark “letters” to the scratches on the bark.

Royal Academy’s #sensingSpaces

In stark contrast, the exhibit at the Royal Academy was extraordinarily uplifting.

I suppose exploring spaces, architecture and design, things designed around humans on purpose, is intended to make an impression on the psyche. Whereas an educational historic exhibit is not.

We walked straight into a bright, well-lit space. The ceilings were extraordinarily high, light was coming in from skylights or high-placed windows, and people were everywhere. Some sitting, some standing, some browsing on iPads, learning about the work of the contributing artists and architects.

We walked into the first room. There was a fort made of wood! It dominated the space, while at the same time being dwarfed by it. This room we were in contained a fort. You could climb up two floors and still not be able to touch the ceiling!

If you climbed to the top, you could peek out from a little window and see this lovely angel up close!

In the room next to it, there was a grotto made of blocks. People had been clutching multi-coloured straws everywhere. I then realised why: they were pieces you could add to the grotto walls. Everyone was picking up those gigantic straws, turning them into bows & arrows, into lampshades, into garlands, into bouquets of flowers. People were interacting with the exhibit, with the space, they were contributing and also taking something away.

I made a little rose, and later handed it to my partner. He didn’t want to take it at the time, so I hid it into the next room’s “forest” walls and took a picture of it.

Within seconds, someone was talking to me, telling me he was cheekily stealing my photo idea. Less than a minute later, as my partner was finally going to photograph and then claim his rose, one man plucked it from the wall and handed it to his girlfriend.

I thought it was the most amazing thing. The five of us had just interacted, been part of a three-fold story. The making and leaving of the rose with photos, the offering, and interrupting the attempt of photography and reclaiming of the rose. This space, this place, had allowed complete strangers to weave stories for each other, and see them. I was on the other side of the “wall” when my partner went to photograph his rose and had to apologise to the guy who plucked it from in front of him. I witnessed the story. And it was the sense of freedom and ownership that allowed us all to experience this.

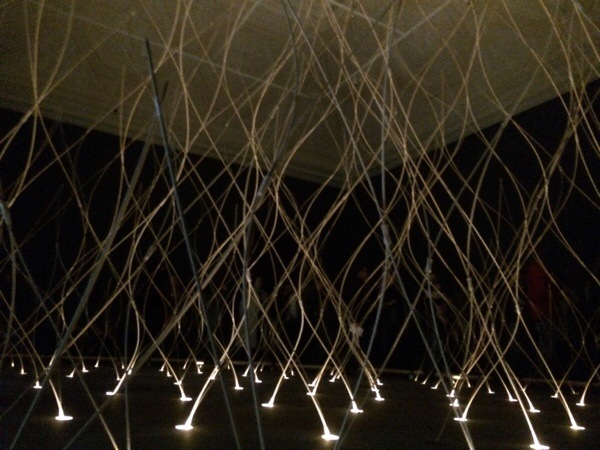

There were other rooms. One played with light, varying where it could go with vertical walls, and changing its direction and intensity constantly. It was living light. Another had smells, that of inoki wood, and that of tatami mats. There were sculptures of the doors of the gallery itself, transposed into the gallery rooms like massive blobs.

(from the room that smelled of inoki wood)

The exhibit was gigantic in real physical size. Seating was available everywhere. You could touch and smell everything. Sit on it. Watch it. It was your space. The feeling when we left was exhilaration, happiness, a broadening of the mind. This was in deep contrast to the exhaustion we had felt the day of the Viking exhibit.

I feel I learned a lot more from experiencing these spaces at the RA than I did learning about decapitation, mass graves, dinars, hoards, torques, and Viking invasions at the British Museum. It is most definitely a false impression, because I know that I have more information in my head from the BM exhibit than I do about the RA one. But somehow, I would recommend the RA experience to anyone and everyone. Whereas I would not want to talk about the Viking exhibit again.

(Did you notice I referred to one as an “experience” and the other as an “exhibit”?)

How people feel after they visit a space that has been designed to be visited is as important as the content. Because my lasting memory of the Viking exhibit was one of tiredness, queuing, eye strain and tediousness. I could not wait for it to finish. Whereas the RA exhibit was exploratory, partly interactive, and I was disappointed when I realised we had visited all of the rooms already.

epilogue, or why museums should consider our feelings

I am currently a member of the Victoria and Albert museum. I adore that place and the exhibits they curate. Of course I do. I care about fashion, design, and the world as seen from our narrow, selfish, human-centred perspective. And I want them to continue doing what they do and showing the world these wonderful things, so I have a membership.

Based on this weekend’s visits, I would also consider becoming a member of the RA, because it inspired me, and made me happy. I would however immediately dismiss any suggestion of becoming a member of the BM. And there were many on our path (an email the day before, an email on the day, and an email the day after, as well as numerous flyers by the entrance and exit), because of how exhausting and ultimately unpleasant visiting was. Not a single seat, for instance, in a 2.5 hour visit.

This is clearly subjective, but so are everyone’s experiences: we are all human, all biased, all somewhat selfish. To me, discovery and surprise matter. The only moment of surprise at the British Museum? Turning a corner and arriving in the gigantic last room, which showcased a 37-metre-long reconstructed Viking warship. It was breath-taking. And it wasn’t enough.

your turn

Do you remember an exhibit you saw recently?

How did you feel after visiting?

Would you become a member of the institution who staged it to ensure they continue their work?